The Cadlas Sourcebook on Investor Stewardship for Climate Resilience

The Cadlas Sourcebook on Investor Stewardship for Climate Resilience: A Practical Resource for Embedding Climate Resilience into Investment Practices

After extensive consultations across the investment industry, Cadlas is pleased to announce the release of our Investor Stewardship for Climate Resilience Sourcebook. This new resource provides a practical framework for investors to align their stewardship practices with climate resilience goals. It lays out how investors can diagnose and understand physical climate risks, prioritise engagement with vulnerable companies and assets, and provide stewardship that drives the adoption of best practices on climate resilience across portfolios.

As the physical impacts of climate change intensify, investors face a defining challenge and opportunity. From floods and wildfires to water stress and heatwaves, physical climate hazards are becoming more frequent, more severe and more financially material. In this context, investors are increasingly recognising that identifying and disclosing physical climate risks is no longer enough. What is required is a shift from risk awareness to resilience action integrated directly into the way investors engage with the companies and assets they own.

The Investor Stewardship for Climate Resilience Sourcebook fills a critical gap in the market for tools and guidance that move beyond disclosure toward actionable investor engagement. It does not seek to reinvent existing investment processes, but instead demonstrates how climate resilience can be embedded within them through flexible and adaptive engagement strategies.

Importantly, the sourcebook builds on the growing body of work developed by leading investment industry bodies in recent years, aiming to advance action by focusing on the specific role investors can play in shaping a climate-resilient real economy.

This work emphasises that promoting climate resilience is aligned with investors’ fiduciary duties, encouraging investors to remain engaged and support climate resilience through targeted stewardship. It also highlights the need for tailored strategies across asset classes and geographies, while offering a curated toolkit of key resources.

By focusing on stewardship as a key instrument for advancing climate resilience, the sourcebook spells out how investors can strengthen long-term performance, manage systemic risks, and contribute to a more resilient and inclusive economy.

As physical climate impacts continue to grow in scope and scale, collaborative stewardship will be essential for unlocking the capital, capabilities, and influence needed to drive meaningful change. The time for passive risk management has passed. Through the release of this sourcebook, Cadlas hopes to contribute towards more widespread investor action that treats climate resilience not as a niche concern, but a core investment imperative.

The Investor Stewardship for Climate Resilience Sourcebook is available for download now.

Cadlas is also pleased to announce our upcoming webinar “Investor Stewardship for Climate Resilience” scheduled for 1pm (BST) on July 16th 2025. Sign up here and stay tuned for more info!

Other Articles

Sustainability-Linked Financing for Climate Resilience (part 2)

In Part 1 of this Resilience Unpacked series on Sustainability-Linked Financing for Climate Resilience, we explored the largely untapped potential of sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) and loans (SLLs) to drive progress on climate adaptation and resilience. Despite their success in supporting mitigation goals, our research found that these instruments have only rarely been used to target adaptation outcomes. However, the growing application of water-related KPIs in SLBs and SLLs may offer a meaningful entry point for change.

In Part 2, we dig deeper into how water-related KPIs and SPTs are currently used in SLBs and SLLs across different sectors. We’ll examine how these indicators map against industry benchmarks, any emerging trends and practices shaping this evolving landscape.

Assembling the Evidence Base

To understand current practices, we analysed a dataset of 151 SLBs and SLLs issued between 2019 and 2024 that included water-related KPIs. This data was sourced from the Environmental Finance Database. Our research focused on four water intensive but key priority sectors: i) agri-processing, ii) manufacturing & services iii) property & tourism and iv) primary agriculture. After filtering out instruments from sectors outside our scope and transactions without disclosed KPIs, we identified 36 relevant SLBs and SLLs comprising 20 bonds and 16 loans for further analysis.

These transactions span a range of sectors and geographies, offering valuable insight into how water-related targets are structured in real sustainability-linked finance deals. They also provide a practical foundation for assessing the ambition and comparability of these targets against established industry benchmarks.

Anchoring to Benchmarks: What’s Available and What’s Missing

One of the key challenges in assessing SPT ambition is the absence of standardised benchmarks across sectors. To address this, our analysis drew on several existing reference points:

- EU BREFs

These are comprehensive, technical resources that detail the Best Available Technologies (BAT) for a plethora of industries. While the focus is on integrated pollution prevention and control across industries, they often include information on energy, water use and wastewater management. These documents offer granular, production process level industry benchmarks that, while useful, require careful interpretation to avoid misapplication outside their specific industrial context. As a result, we based our analysis on BREF water benchmarks.

- Buildings industry benchmarks

We referenced environmental benchmarks developed by the Better Buildings Partnership (BBP) to support our analysis of the property & tourism sector. These provide practical environmental benchmarks for commercial buildings, such as offices and shopping centres. However, their specificity to commercial buildings such as office blocks and shopping malls means they are not directly applicable to other building types like residential buildings.

- Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) resources

We reviewed water-related data and guidance from the FAO AQUASTAT database as well as other FAO resources to support our analysis of the primary agriculture sector. While rich in information, methodological uncertainties around target-setting in primary agriculture prevented us from fully integrating these benchmarks into our analysis.

Water-Related KPI Categories in Practice

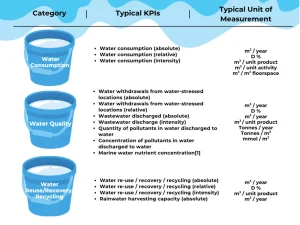

Our analysis revealed that water-related KPIs in SLBs and SLLs generally fall into three main categories: water consumption, water quality, and water reuse/recovery/recycling.

Water Consumption: These KPIs are the most widely used. These may be measured in absolute terms (e.g. cubic metres per year), in relative terms (e.g. percentage reduction in water consumption), or in terms of intensity – for example, water consumption per unit of product in manufacturing, per unit of activity in services, or per square metre in real estate. Some KPIs also focus specifically on water consumption from water-stressed regions, either in absolute or relative terms.

Water Quality: These KPIs tend to focus on the volume of wastewater discharged, either in absolute terms or in specific intensity terms and are commonly cited in BREFs. Some KPIs are qualitative and used to measure the wastewater pollutant load in terms of pollutant quantity or concentration.

Water Reuse/Recovery/Recycling: These KPIs are used in several sectors. These may be framed in absolute, relative, or intensity terms. A few transactions also include rainwater harvesting targets, although these are less common.

Table 1: Categorisation of water-related KPIs identified in the evidence base

Assessing Target Ambition: The Role of Second Party Opinions

In the absence of universally accepted benchmarks, SPTs in SLBs and SLLs are typically assessed by Second Party Opinion (SPO) providers. These providers use qualitative categories such as “insufficiently ambitious,” “moderately ambitious,” “ambitious,” and “highly ambitious” to rate the strength of a given target. While methodologies vary and are not always disclosed in full, two criteria consistently emerge.

First, SPOs often assess whether the target represents a meaningful improvement on the issuer’s past performance. This relies on transparent reporting of historic water use, which can be a challenge for some companies. Second, SPOs consider whether the target exceeds what is typical for the issuer’s sector. This comparative analysis depends on the availability of peer targets or recognised benchmarks, which are uneven across sectors.

Together, these criteria underscore the importance of both internal and external reference points in credible SPT design and the need for more consistent disclosure and benchmarking tools.

Sector-Specific Trends and Observations

The 36 SLBs and SLLs analysed reveal some important sector-level differences in how water-related KPIs and SPTs are used.

In the Agri-Processing sector, most water targets relate to consumption intensity, particularly in the beverage production sub-sector. Here, an ambitious target often involves a 10–20% reduction in water consumption intensity per unit (litre) of product. EU BREFs for the food, drink and milk industries also provide useful benchmarks for wastewater discharge intensity per unit of product, particularly in industries like brewing.

The Manufacturing & Services sector is highly diverse, spanning industries as different as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, paper & packaging, mining and logistics & services. Water KPIs here cover a broad range from water consumption in absolute terms in pharmaceutical production to wastewater discharge intensity in chemicals, plastics & rubber and paper & packaging, as well as water reuse/recovery/recycling in logistics & services. Given this diversity, setting credible targets requires deep industry-specific knowledge and benchmarking.

In the Property & Tourism sector, water consumption intensity is the dominant metric. Here, BBP benchmarks offer a relatively robust reference point for target setting. There is also at least one example of targets related to rainwater harvesting, although such these remain rare.

In contrast, the Primary Agriculture sector remains largely absent from the sustainability-linked finance landscape when it comes to water KPIs. Despite agriculture being the largest consumer of freshwater globally, our analysis found only one SPT in the livestock sub-sector, targeting absolute wastewater discharge. No examples were found for crop production despite it requiring the most significant amounts of water. While the ICMA KPI Registry provides many KPI recommendations, our research found little evidence of their practical use to set SPTs.

Looking Ahead

Our analysis across this Resilience Unpacked series highlights both the progress and the gaps in how water-related KPIs are used in SLBs & SLLs. While levels of rigour and benchmarking vary, what’s clear is that water offers a unique entry point for linking finance to resilience outcomes. Water is deeply connected to the impacts of climate change and increasingly measurable through performance-based metrics making it a natural candidate for integrating adaptation goals into mainstream financial instruments.

If we are to unlock the full potential of sustainability-linked finance for climate resilience, water-related KPIs could help lead the way. They offer a concrete, scalable foundation on which to build stronger, more credible frameworks that channel capital towards adaptation.

Thank you for following along with this Resilience Unpacked series on Sustainability-Linked Financing for Climate Resilience. Stay tuned for more from our Resilience Unpacked insights series and more!

Other Articles

Sustainability-Linked Financing for Climate Resilience (part 1)

Welcome to the second instalment of Resilience Unpacked, Cadlas’ insights series exploring key topics in climate resilience finance. In this edition, we examine sustainability-linked financing and its potential to support greater private investment in climate adaptation.

Results-based financing mechanisms such as Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) and Sustainability-Linked Loans (SLLs) tie financial terms to the achievement of sustainability goals. This creates incentives for companies to meet environmental performance targets. If structured around climate resilience-related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), these instruments could channel much-needed private capital into adaptation measures at the corporate and entity level while setting powerful incentives for improving corporate performance on climate resilience.

Despite their growing popularity in supporting mitigation-focused corporate sustainability goals, SLBs and SLLs rarely incorporate adaptation and resilience objectives. This represents an underutilised opportunity to drive progress on adaptation and resilience. However, there may be important lessons from the application of sustainability-linked instruments in water-related investments that provide avenues for their potential role in financing climate resilience.

What are SLBs and SLLs?

Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) are general-purpose bonds that link financing terms, such as interest rates, to the achievement of predefined sustainability-related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). If an issuer meets or falls short of its sustainability targets, financial terms may be adjusted accordingly.

Sustainability-Linked Loans (SLLs) function similarly but are structured as loans between a given lender and a given borrower, rather than bonds which are issued to raise funds from capital markets. Their terms also adjust based on performance against agreed sustainability KPIs.

Both instruments present an opportunity to incentivise investment in resilience by directly tying financing terms to progress on climate adaptation metrics. However, this opportunity has not been widely utilised across markets.

Limited Usage of Adaptation & Resilience Related KPIs

Despite the surge in sustainability-linked finance, adaptation KPIs remain strikingly rare. Research by Cadlas into global SLB issuances, using the Environmental Finance Database, found no examples of any specific adaptation or resilience KPIs included in global SLB issuances to date.

This trend was also observed in SLLs, with our research finding only one instance of climate adaptation as a KPI. HB Reavis, a UK-based real estate firm, secured a USD 32.4 million SLL in February 2024, which included a KPI linked to the number of EU Taxonomy-aligned buildings designed for climate adaptation. However, limited public information makes it hard to assess the robustness of this KPI.

This scarcity suggests potential uncertainty among issuers about how to define, implement, and measure adaptation KPIs. One key barrier is an unaddressed need for standardised guidance for adaptation-related KPIs in sustainability-linked finance.

Need for Clearer Guidance on Target Setting for Adaptation & Resilience

The International Capital Market Association (ICMA), a globally recognised standard-setting body, currently provides a limited number of KPIs that could convincingly be considered adaptation-related in the June 2024 iteration of its KPI Registry.

These are found in the Energy and Insurance (assets) sectors, representing only two out of ICMA’s twenty-six sectors. Within the Energy sector the adaptation-related KPI related to Share of energy produced in alignment with the EU Adaptation Taxonomy. While the KPI for the Insurance (assets) sector referred to the Proportion of invested assets managed with climate adaptation objectives.

Beyond these, ICMA lists three additional KPIs loosely linked to adaptation and all found within the Utilities (electricity) sector, but these lack clear resilience-focused outcomes. These include:

- Increase additional transformer capacity to facilitate interaction with the grid and integrate renewable energy generation,

- Increase power usage effectiveness/efficiency

- Renewable energy capacity (absolute or proportional).

This highlights the need for more detailed, targeted guidance on adaptation-related KPIs that are suitable for use in sustainability-linked debt instruments. Such guidance could build on existing best practices in financial sector adaptation and resilience metrics, such as the ARIC Adaptation & Resilience Impact Measurement Framework for Investors, developed in collaboration with UNEP-FI and Cadlas.

Water KPIs as a Proxy for Resilience in SLBs and SLLs

While adaptation-focused KPIs remain largely absent, water-related KPIs have gained significant traction, potentially serving as a stepping stone for broader resilience financing.

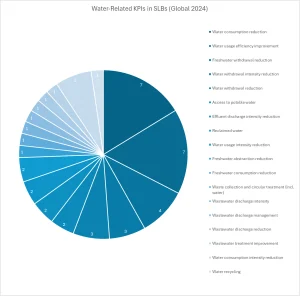

According to the Environmental Finance Database in 2024 there were:

- 43 SLBs valued at nearly USD 72 billion were issued globally with water-related KPIs by corporate borrowers

- The most common KPIs included water consumption reduction, efficiency improvements, and freshwater withdrawal reduction.

While several transactions did not specify precise bond KPIs, SLBs were categorised and grouped based on existing loan KPI details from the Environmental Finance Database and where possible, financing frameworks and other relevant publicly available documents.

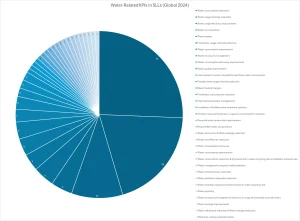

Water-Related KPIs in SLBs (Global Issuance, 2024)

The use of water-related KPIs appeared to be even more prevalent in SLLs, suggesting a stronger link between water management and this approach to sustainability-linked financing.

- 137 SLLs globally included water-related KPIs.

- The total lending volume of these SLLs reached USD 82.0 billion.

Of the one hundred and thirty-seven SLLs tagged by Environmental Finance as having water-related KPIs, only 121 could be categorised.

Water-Related KPIs in SLLs (Global Issuance, 2024)

Water-Related KPIs in the ICMA SLB KPI Registry

The water-related KPIs found in SLBs and SLLs from the Environmental Finance Database align closely with those listed in the ICMA SLB KPI Registry across a wide range of sectors including automotive, construction, energy, food and agriculture, finance, food & beverages, manufacturing, healthcare, maritime, metals & mining, retail, real estate, technology, transportation and utilities.

Across these sectors, water-related KPIs typically fall under six broad categories illustrated in the image below:

Six Categories in the ICMA SLB KPI Registry

These KPIs highlight the capacity for water to be used as a measurable, trackable and financeable resilience theme. However, while these KPIs offer a solid foundation, setting Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs) against them remains a challenge.

From KPI to Impact: Driving Resilience & Improving Investor Confidence

Although water-related KPIs are common, the next hurdle is setting credible Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs). SPTs tend to vary widely by issuer, sector and local context, and there is currently no standardised guidance for setting benchmarks or thresholds, especially for SLLs, where SPTs are rarely disclosed. This limits confidence and consistency across the market.

Despite this uncertainty around benchmarking & target-setting, SLBs still offer a powerful mechanism to incentivise financing broader resilience outcomes including water resource management.

The Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute (AFII) in their article ‘Rebuilding Confidence in the UK Water Sector,’ highlight the role SLBs can play in helping embattled UK water companies drive greater transparency on sustainability challenges, while also providing a financial hedge against poor performance for investors. AFII points out that by directly linking the cost of capital to measurable sustainability targets, water companies can improve investor confidence and build accountability.

Looking Ahead

At Cadlas, we are committed to driving innovation in sustainable finance that supports climate adaptation and resilience. One promising pathway lies in strengthening the design of SLBs and SLLs through more robust and relevant target-setting approaches. Developing clearer guidance for setting SPTs for water-related KPIs could be a practical and high-impact next step. This would not only reinforce the resilience link within SLBs and SLLs but also help build issuer and investor confidence in the adaptation value of these instruments.

By addressing these technical and strategic barriers, sustainability-linked finance can evolve into a more powerful mechanism for mobilising private investment in adaptation and resilience efforts. Water-related metrics, in particular, offer a compelling entry point for advancing this agenda. By anchoring SPTs in credible water-related KPIs, issuers can begin to demonstrate how sustainability-linked finance can deliver measurable adaptation outcomes. In doing so, they can help pave the way for wider market recognition of the role SLBs and SLLs can play in scaling climate resilience.

What’s Next?

In Part 2 of this Resilience Unpacked series on sustainability-linked finance, we’ll take a closer look at how water-related KPIs and SPTs are currently used in SLBs and SLLs across different sectors. We’ll examine how these indicators map against industry benchmarks, as well as analyse emerging trends and practices shaping this evolving landscape.

Other Articles

Insights from Resilience Unpacked: The Role of National Platforms in Unlocking Adaptation Investment

Insights from Resilience Unpacked: The Role of National Platforms in Unlocking Adaptation Investment

As climate risks intensify, the need to channel finance into adaptation has never been more urgent. Yet, despite more than a decade into formal national adaptation planning, implementation continues to lag behind. Cadlas’ recent webinar and panel discussion brought together leading experts Nanki Kaur from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Michael Mullan from the Organisation of Economic Cooperation & Development (OECD), Bouke de Vries, independent expert and former advisor to the Executive Board of Rabobank and Danielle Evanson from the Government of Barbados’ Roofs-to-Reefs programme to explore how countries can and are already utilising national platforms to turn high-level adaptation policies into investment-ready strategies.

Unlocking the Potential of National Adaptation Plans (NAPs)

Nanki Kaur highlighted how National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) offer countries a structured way to assess climate risks and set sector-specific adaptation priorities. When done well, NAPs guide policy direction and investment planning, helping governments articulate both the urgency and strategic direction of their adaptation needs.

But turning these plans into investable projects is easier said than done. As Nanki pointed out, despite years of planning, adaptation financing remains elusive due in part to poor translation of climate risks into metrics that matter to investors. Many NAPs contain fragmented, small-scale solutions that fail to tackle adaptation at a systems level, and crucially, they’re often not well integrated into national public investment systems.

Making the Economic Case for Adaptation

Nanki also highlighted that one of the biggest challenges for countries has been demonstrating the value of adaptation. While there are many examples of economic modelling showing the costs of not adapting, very little analysis continues to be done on the benefits of proactive adaptation. This gap makes it harder for Ministries of Finance to justify adaptation investments or for private investors to see a business case for investing in adaptation.

To address this, ADB is supporting fourteen countries through its Climate Adaptation Investment Planning (CAIP) programme. This initiative focuses on aligning adaptation plans with public financial management systems and embedding economic analysis to assess the fiscal and financial returns of adaptation investment. This will in turn help governments to prioritise public funds where they are needed most, while steering viable projects towards private finance.

Building Institutional Architecture for Investment

Similarly, Michael Mullan underscored that effective adaptation planning requires robust cross-government coordination. While leadership often starts within specific ministries or agencies, unlocking finance and shifting national budgets requires collaboration from across all sectors and levels of government.

The OECD’s Climate Adaptation Investment Framework (CAIF) identifies six building blocks to integrate adaptation into investment planning including public finance mainstreaming, private investment support and sectoral regulation. To make this work, all parts of government need to be aligned. National platforms, Michael noted, can play a key role in strengthening institutional mechanisms, integrating climate risk into central government mandates and providing clearer planning signals to investors.

Lessons from Barbados’ Integrated Approach to Adaptation & Resilience

Danielle Evanson shared how Barbados is leading with an integrated, national platform approach through its “Roofs-to-Reefs” initiative. Rooted in the idea that climate resilience must stretch from households to coral reefs, the programme sits within the Prime Minister’s Office, enabling high-level coordination and oversight.

Roofs-to-Reefs operationalises adaptation planning by linking national policies, such as the Barbados Economic Recovery and Transformation (BERT) plan and Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) with investment plans across six priority sectors including water, energy, waste, land use, ecosystems and housing. Importantly, this approach blends public and private investment, guided by a unified national vision.

Barbados has also turned to innovative financing tools to scale impact, structuring debt-for-nature and debt-for-climate swaps that mobilised investment from multilateral banks and domestic financial institutions. These mechanisms facilitated the establishment of the Barbados Environmental Sustainability Fund and the Blue Green Investment Bank, which is now in its operationalisation stage.

Engaging the Private Sector: Insights from the Netherlands

Bouke de Vries brought a unique perspective from the Netherlands Sustainable Finance Platform (SFP) convened not by a ministry, but by the Dutch Central Bank. The SFP aims to bring together stakeholders from the financial sector, government and scientific institutions to promote sustainability in the Netherlands. The platform makes recommendations for removing barriers to sustainable finance and is actively involved in pilots for sustainability initiatives.

In the SFP’s Climate Adaptation Working Group, members discuss what is needed to accelerate climate adaptation at the national level, with a particular focus on private sector stakeholders. Notably, this working group also includes the secretariat of the National Delta Programme’s commissioner.

Bouke highlighted that climate change poses a systemic risk which also affects the financial sector. It must therefore understand and manage these risks within its assets and client portfolios, with banks, insurers and institutional investors assessing, pricing, transforming, or avoiding them. Additionally, the financial sector contributes to adaptation and resilience by financing adaptation investments and insuring against risks. These are also important commercial opportunities.

Clear labels and taxonomies provide both urgency and clarity by helping to translate climate data into meaningful signals for market actors that can inform investment decisions. Well defined and actionable national adaptation strategies and targets are much needed to make adaptation more investable and bankable, as well as communication to businesses and people to raise awareness, enabling regulation and policies.

A Systems Shift Is Underway

If there was one overarching theme from the panel, it’s that climate adaptation can no longer be treated as an isolated policy issue. It must be understood as a systems issue, one that spans ministries, markets and entire economies.

Whether through national platforms like Barbados’ Roofs-to-Reefs, cross-sectoral coordination frameworks championed by the OECD, or regional investment planning supported by ADB, the shift from planning to financing adaptation is gaining traction. But for these efforts to succeed, countries must not only clarify their priorities they must also build the economic and institutional foundations that enable investment to flow.

Other Articles

Adaptation Finance becomes a highlight at UNEP FI Regional Roundtable

Adaptation Finance becomes a highlight at UNEP FI Regional Roundtable

Imagine a future where the financial sector is a powerful engine driving climate resilience across Latin America and the Caribbean. At Cadlas, we’re not just imagining it – we’re working to make it a reality!

Last week, our team had the privilege of helping to deliver the “Scaling Up Climate Adaptation Finance” workshop at the UNEP FI Regional Roundtable on Sustainable Finance in São Paulo. The room was buzzing with energy as participants from across the region came together to tackle one of the most pressing challenges of our time.

Collaboration is Key

Throughout the roundtable, we engaged in deep discussions on physical climate risk and adaptation finance.

A key takeaway? Collaboration is essential. By facilitating peer-to-peer dialogues and knowledge exchange, we saw firsthand how bringing diverse perspectives to the table can spark transformative ideas and solutions.

Piecing Together the Adaptation Finance Puzzle

So, what does it take to scale up adaptation finance? Our workshop participants identified several critical pieces of the puzzle:

- Locally-relevant taxonomies: Adaptation finance frameworks must be co-created with stakeholders to reflect the diverse realities on the ground.

- Alignment with policy: Embedding adaptation taxonomies within national policy instruments like NAPs is key for coherence and impact.

- Measuring what matters: Incorporating resilience and risk reduction KPIs into taxonomies can drive accountability and help track progress against adaptation goals.

- Growing the market: Capacity building and awareness-raising efforts are needed to position adaptation finance as a win-win for risk management and value creation.

Bridging Insights to Action

At Cadlas, we’re committed to turning these insights into action. That’s why we’re proud to be collaborating with the Climate Bonds Initiative on the groundbreaking Climate Bonds Resilience Taxonomy.

This taxonomy will provide a robust framework for identifying and scaling up climate resilience investments. And guess what? It’s grounded in the same principles of inclusivity, alignment, impact, and market development that emerged from the UNEP FI roundtable.

The Path Forward

As we continue to advance the Climate Bonds Resilience Taxonomy and engage with partners worldwide, one thing is clear: the sustainable finance community is a force to be reckoned with.

Together, we have the power to mobilize the capital needed to build a more resilient future for all. So, let’s keep breaking down silos, pushing boundaries, and daring to imagine a world where finance and sustainability go hand in hand.

Stay tuned for more updates on our work to scale up adaptation finance through the CAIL community of practice. And if you’re ready to join the movement, drop us a line! We’d love to explore how we can collaborate to drive climate resilience in Latin America, the Caribbean, and beyond.

Other Articles

National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience (Part 2)

Welcome to the second instalment of Cadlas’ new insight blog series, Resilience Unpacked, where we explore key topics in climate resilience financing. In this edition, we focus on National Platforms for Adaptation and Resilience Investment.

National platforms or country platforms for climate action are country-led partnerships that align financing, coordinate stakeholders and connect national climate policies with financeable projects. They enhance collaboration, streamline funding and maximise climate impact by bridging the gap high-level national adaptation plans and financeable investments.

As demand for adaptation finance grows globally, national platforms are increasingly identified as important mechanisms for mobilising investment in climate adaptation and resilience initiatives. Strengthening and expanding these platforms will be key to transforming national climate policy ambitions into investable projects and unlocking the full potential of climate resilience investments for a more resilient future.

In Part 1 of our Resilience Unpacked series on national platforms, we explored exactly what they are and how they function. Now, we’ll take a closer look at their structure, organisation and the key stakeholders driving their work. Click here to read part 1 of this series

Structure of National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience

As explored in Part 1, national platforms for climate action integrate climate considerations into investment pipelines by embedding them into strategy, operations and decision-making processes.

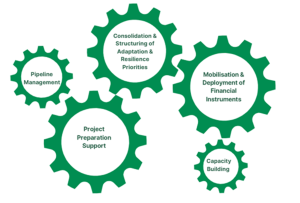

While there is no universal model, these platforms typically achieve their objectives by consolidating national climate priorities, supporting project preparation and capacity building, enhancing project pipeline management and mobilising innovative financial instruments.

A defining characteristic of national platforms is that they are country-driven, meaning their structure varies based on national context. Despite differences in governance and institutional setup, these platforms generally engage a diverse set of stakeholders, including government entities, the private sector, civil society (including academia), and, in many cases, international organisations.

Stakeholder Roles in National Platforms

Stakeholders within national platforms work together to set the platform’s strategic direction, align investments with national adaptation priorities, mobilise funding, and develop investable adaptation project pipelines.

They also build institutional capacity, manage risks, coordinate community engagement to ensure local adaptation needs are met, and streamline funding between national governments and international financial institutions. These stakeholders generally fall into two main categories: leading and supporting stakeholders.

Leading Stakeholders

- Leading stakeholders play a key role in integrating national adaptation priorities into investment planning and financial supervision.

Supporting Stakeholders

- Supporting stakeholders help incorporate adaptation into sectoral investment planning and align community-level adaptation goals with national priorities.

- Depending on the institutional context, there may be other supporting stakeholders which contribute by managing risk and data, aligning projects with finance priorities, coordinating international funding, providing climate risk modelling, and promoting equity in adaptation efforts.

National Platforms in Action: Examples from Around the World

While national platforms have been widely used to support climate mitigation efforts, not many examples exist of their application in scaling up finance specifically for adaptation and resilience. However, international support for adaptation-focused national platforms is growing, with a consortium of MDBs publishing guiding principles for their development and implementation.

Key initiatives driving this momentum include the:

- Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) Climate Adaptation Investment Planning (CAIP) , which helps ADB partner countries translate national adaptation priorities into robust investment programmes by leveraging existing structures and strategies.

- International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF ), which provides long-term financing to help countries strengthen economic resilience to climate risks.

As mentioned previously, the structure of a national platform varies based on country-specific needs and governance models. The following examples illustrate these differences, showcasing distinct stakeholder roles and levels of involvement.

The Netherlands Sustainable Finance Platform

Chaired by the De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), the Netherlands’ Sustainable Finance Platform (SFP) is a great example of a financial sector driven national platform. The SFP brings together stakeholders across the financial sector including asset managers, the Dutch Banking Association, insurers and pension funds to work with government ministries to promote sustainability in the Netherlands through its financial sector.

A core feature of this platform is its working groups, which shape the platform’s thematic focus. Importantly, the SFP features an Adaptation Working Group which examines how the financial sector can support economic adaptation to climate change in four key sectors: built environment, agriculture, industry and transport. The group assesses scenarios, methods, and data required for financial institutions to evaluate climate risks and adaptation needs. While its outcomes are non-binding, its recommendations play an important role in strengthening collaboration between financial institutions, the government, and other stakeholders, ensuring that adaptation challenges are linked to financial sector actions.

The Bangladesh Climate and Development Platform

Bangladesh is among the most climate-vulnerable nations, making climate adaptation finance an urgent priority. Launched in 2023, the Bangladesh Climate and Development Platform (BCDP) is a government-led initiative established in collaboration with international financial institutions, bilateral donors, and the private sector. While not exclusively focused on adaptation and resilience, the platform aims to generate a robust pipeline of climate projects and financing strategies.

Building upon financing from long-term international development financing partners and an arrangement with the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Facility, the BCDP aims to improve the integration of climate risks into fiscal planning, enhance climate-sensitive public investment management and strengthen climate-related risk management for financial institutions. Under the BCDP, a project preparation facility will also be established to enhance project bankability, making climate projects more scalable and attractive to private investment.

The Way Forward for National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience

By streamlining stakeholder collaboration, national platforms have become important mechanisms for mobilising finance for adaptation & resilience. The examples of the Netherlands and Bangladesh highlight how platforms can be tailored to meet country-specific needs to build resilience to the growing challenges of climate change.

As the demand for adaptation finance continues to rise, the success of these platforms will depend on strong, inclusive partnerships and a clear focus on locally led solutions.

This concludes our Resilience Unpacked series on National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience. Thank you for joining us on this deep dive into national platforms and stay tuned for more from the Resilience Unpacked blogs series!

Other Articles

National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience (Part 1)

Welcome to the first instalment of Cadlas’ new insight blog series, Resilience Unpacked, where we explore key topics in climate resilience financing. In this edition, we focus on National Platforms for Adaptation and Resilience Investment.

We’ll explore how these platforms can serve as crucial mechanisms for financing climate adaptation and resilience initiatives. Specifically, we’ll define what they are and examine how they function, while highlighting the key role they can play in mobilising finance for adaptation and resilience.

What Are National Platforms and Why Do They Matter for Adaptation & Resilience?

National Platforms for climate action, or more commonly called country platforms, are government-led partnerships that bring together multiple stakeholders including the private sector and development finance partners to coordinate efforts, align financing and support national priorities. They act as investment coordination hubs, connecting national climate policies with financeable projects by fostering collaboration, streamlining funding and enhancing the impact of climate-focused development initiatives.

Mobilising Finance for Adaptation & Resilience

Regarded as key coordination mechanisms, national platforms have begun to play an increasingly vital role in advancing national climate goals. Their significance was underscored in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) 2023 Global Stocktake, where they were highlighted as instrumental in facilitating the implementation of the third round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). But how do they relate to adaptation and resilience?

While many of these platforms focus primarily on climate mitigation, such as the International Partners Group (IPG) supported Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), national platforms also have the potential to play a crucial role in scaling up and mobilising finance for adaptation and resilience. They can offer focus and ownership over national and local adaptation priorities and coordinate investment efforts by bridging the gap between high-level adaptation strategies, like National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), and financeable investments.

The diagram below illustrates how national platforms can utilise country-level strategies to align financial flows with adaptation needs:

Mainstreaming Adaptation & Resilience Across the Investment Pipeline

National platforms mainstream adaptation and resilience considerations across the investment pipeline by integrating it into their strategy, operations, and decision-making processes. They achieve this via three key functions: Strategic Planning & Policy Integration, Investment Structuring & Financial Alignment, and Enabling Environments & Capacity Building.

The diagram below illustrates how national platforms function by integrating and mainstreaming adaptation and resilience considerations across the investment pipeline:

Strategic Planning & Policy Integration

National platforms play a vital role in turning national adaptation policies into investable plans and mobilising the necessary domestic and international resources. They create opportunities for government bodies, such as finance ministries, to collaborate with key stakeholders, ensuring adaptation and resilience are embedded into public investment programmes. By translating physical climate risks into investment priorities, they help develop pipelines that align with the risk-return expectations of financiers, making adaptation a more attractive and viable investment.

Investment Structuring & Financial Alignment

National platforms support the structuring of investment programmes that blend public, private and concessional finance to crowd-in commercial capital and ensure that investments meet investor requirements. They also help capture and monetise the full range of adaptation benefits including avoided losses, enhanced resilience and broader sustainable development benefits, strengthening the business case for investment. They also facilitate the integration of adaptation and resilience metrics into investment appraisal frameworks, ensuring that projects can be matched with the right financial instruments and capital types, making it easier to mainstream adaptation into investment decisions.

Enabling Environment & Capacity Building

Beyond finance, national platforms help establish the necessary, enabling environment for adaptation investment through facilitating technical assistance, promoting the development of metrics/standards and promoting the integration of adaptation and resilience into financial supervision. They also play a key role in supporting project preparation, building institutional capacity and fostering knowledge sharing across the financial sector.

Looking Ahead – Strengthening National Platforms for Climate-Resilient Growth

In conclusion, national platforms have the potential to be powerful drivers of adaptation and resilience finance, turning policy ambitions into investable projects.

By integrating adaptation and resilience considerations across the investment pipeline, they foster collaboration, align financial flows and embed adaptation and resilience into national investment decision-making. As the need for adaptation finance continues to rise, strengthening and expanding these platforms will be key to unlocking the full potential of climate resilience investments and building a more climate-resilient future.

To scale climate adaptation finance, national platforms must:

- Expand beyond being primarily mitigation-focused and fully integrate adaptation & resilience

- Align financial flows with adaptation goals for long-term climate security

- Strengthen cross-sector collaboration to foster holistic adaptation strategies

By providing a holistic overview of key stakeholders’ inputs and country needs, national platforms help direct financial flows and facilitate partnerships.

In part 2 of this Resilience Unpacked series on National Platforms, we’ll dive deeper into how National Platforms are structured and organised, and the various kinds of stakeholders that are involved. Stay tuned!

Other Articles

The Role of GSS+ bonds in Mobilising Finance for Adaptation & Resilience

The Role of GSS+ bonds in Mobilising Finance for Adaptation & Resilience

The Need for Adaptation Finance

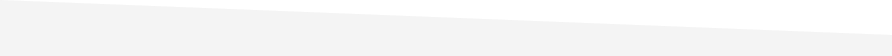

The Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) reports that global climate finance flows surged to nearly $1.3 trillion USD in 2021/2022. This growth was mainly driven by a significant rise in mitigation finance directed towards renewable energy and transport sectors in countries like China, the United States, Europe, Brazil, Japan, and India. Adaptation finance also saw a moderate increase, climbing from $49 billion USD in 2019/2020 to $63 billion USD in 2021/2022.

Adaptation Gap Report 2023 | UNEP – UN Environment Programme

However, despite this encouraging trend, adaptation finance remains just a small fraction of the total global climate finance pie. As climate change becomes increasingly difficult to both mitigate and adapt to, closing the global adaptation finance gap is crucial. CPI estimates that developing countries will need $212 billion USD annually up to 2030 to adapt to the rapidly changing climate, with African countries alone requiring at least USD $52 billion per year until 2030.

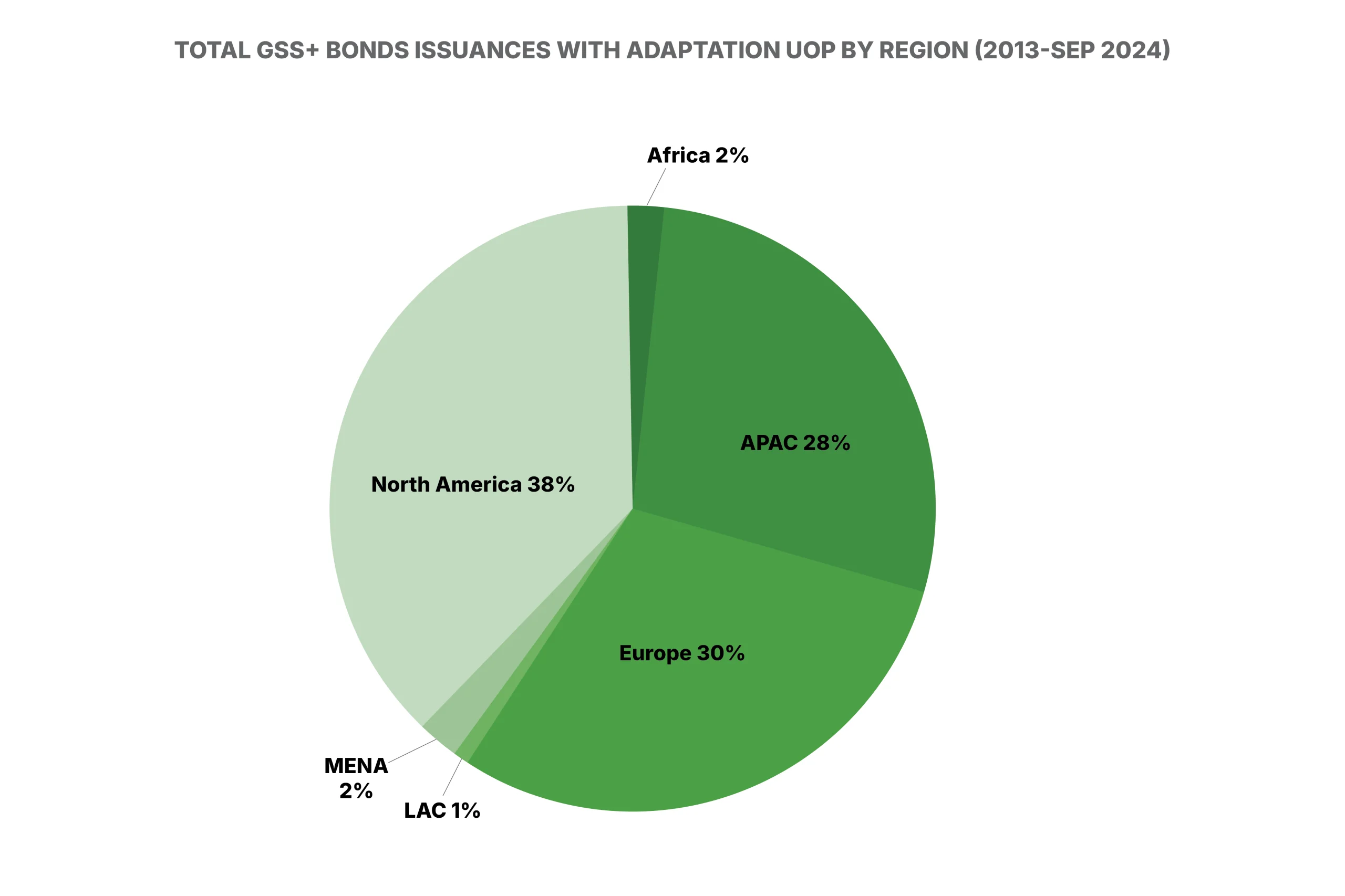

This underscores the urgent need for innovative financing instruments to support adaptation efforts. One promising solution is the use of green, social, and sustainability (GSS+) bonds that incorporate adaptation and resilience as eligible uses of proceeds (UoP). This market has seen rapid growth, with over 2500 GSS+ bonds with adaptation issued at a volume of just over USD $1 trillion since Sweden’s City of Gothenburg first included adaptation as an eligible UoP in its 2013 green bond issuance.

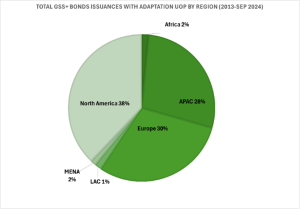

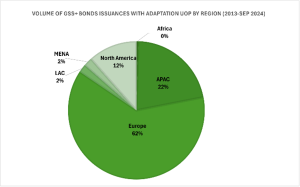

Cadlas recently conducted research into GSS+ bonds with adaptation UoP over the period 2013 to September 2024, using data from the Environmental Finance database. This examined trends in the volume of GSS+ bond issuances as well as the total number of issuances across various issuer types including sovereign, sub-sovereign (agency & municipal), corporates, financial institutions and supranational entities. Below is a brief breakdown of our major findings:

Global Trends

High-Income and Upper-Middle Income Countries:

Issuers in high and upper-middle income countries have mobilized over $620 billion from 1,657 bonds between 2013 and September 2024. Europe leads with over $430 billion from 557 bonds, while the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region follows with just over $110 billion from 383 bonds. North American issuers accounted for approximately 42% of the bonds issued in the region, but only mobilized about $70 billion in total. Municipal entities in the U.S. were responsible for nearly half of the total issuances, although their bond volumes were smaller compared to European sovereign issuances, which made up over 60% of that region’s volume.

Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries

In contrast, low and middle-income issuers have contributed 219 bonds valued at $72 billion. The APAC region stands out, accounting for over 60% of total bonds issued and 55% of the total volume. Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) followed with nearly 20% of the volume, while Africa accounted for 13% of all issuances but only 4% of the volume, reflecting a predominance of smaller bond issuances in the region.

Regional Trends

APAC:

The APAC region has mobilized over $140 billion from approximately 523 bonds. Countries like Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Australia collectively accounted for nearly 70% of the bond issuances during this period.

Africa:

Africa saw just over $3 billion from 27 bonds, primarily driven by South African financial institutions, which made up 65% of the bond volumes.

Europe:

In Europe, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and France led in the number of bonds issued, with sovereign bonds accounting for 72% of the region’s total volume despite making up only 29% of total issuances.

LAC:

Brazil dominated the LAC region, issuing 10 of the 28 bonds and generating the highest volume, while Colombia followed with 8 sovereign bonds.

MENA:

The MENA region’s landscape included 6 sovereign bonds and 16 issued by financial institutions, with the UAE leading in volume.

North America:

North American bond issuers accounted for approximately 712 bonds, generating over $80 billion in volume. The U.S. dominated in bond issuances, especially among municipal entities.

Conclusion

While adaptation finance still represents a small fraction of global climate finance, the growth of GSS+ bonds signify a positive trend in bridging this adaptation finance gap, particularly in developing countries. As awareness of climate resilience and its importance continues to grow, GSS+ bonds can become a vital instrument in mobilizing in adaptation initiatives.

Other Articles

Insights from Climate Bonds CONNECT 2024: Fostering Resilience in a Changing World

Insights from Climate Bonds CONNECT 2024: Fostering Resilience in a Changing World

From discussions about transition planning for corporates to the path to achieving interoperability and innovative models for scaling up finance for resilience, Climate Bonds CONNECT 2024 was filled with valuable insights and impactful discussion sessions around adaptation and resilience.

The jam-packed day began with Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) CEO, Sean Kidney’s opening speech where he emphasized the need for global effort on building resilience to climate change given that it is a global challenge.Furthermore, efforts to avoid catastrophic climate change continue to be hindered by a range of crises, including socioeconomic inequality, health and food security concerns, all of which are exacerbated by climate change itself. These challenges require international cooperation and coordination, particularly around adaptation and resilience.

Mr. Kidney underscored this point by noting that climate change will adversely impact the planet irrespective of global progress on mitigation/decarbonisation. As a result, it is necessary now, more than ever to scale up action on adaptation and resilience. While the challenges around decarbonisation/mitigation are well documented this is not the case for resilience/adaptation. However, he noted that tools like CBI’s recently launched Climate Bonds Resilience Taxonomy, for which Cadlas served as the lead technical partner, provide important guidance and clarity on a range of urgent priorities for building resilience. In closing out his speech Mr. Kidney said that despite the enormity of the challenges surrounding climate change, he is still hopeful that we can work together to find a solution. He pointed out that “we are a hive species” intimating our need to work collectively to solve global challenges and cited the ‘green revolution’ and the role of technology as great opportunities.

Immediately following Mr. Kidney’s speech was Torsten Albrecht, Principal Investment Officer at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), who spoke about AIIB and the role of multilateral development banks (MDBs) in supporting the green, social and sustainable (GSS+) bonds market, particularly in emerging economies. He highlighted AIIB’s goal to achieve sustainable economic development through infrastructural projects and the bank’s work to actively scale up private sector participation in climate focused projects. Mr. Albrecht noted that despite the encouraging growth of the GSS+ bonds market in developed markets, there is still a sizeable finance gap and more focus should be placed on emerging markets to help close this gap. This was followed by session 1, a panel discussion on opportunities for corporates and countries around transition planning.

After a brief networking and coffee break, attendees were back in the plenary for session 2 on interoperability between taxonomies which was moderated by CBI’s Director of Thought Leadership, Anna Creed. There are over 45 national or regional taxonomies in existence across the globe, with more in development. While this is necessary given the range of geographical contexts and differing levels of development, it presents a significant reporting challenge to investors and regulators. Panellists highlighted the need for and importance of comparability, equivalence and disclosures in achieving interoperability between taxonomies. Following this was a networking lunch which preceded the second 5-minute OnSwitch session on the Asian Development Bank’s work in the GSS+ bonds market in Southeast Asia.

Immediately after this was what CEO Sean Kidney pointedly referred to as the most highly anticipated session of the day. Session 3 was entitled ‘Innovating for Resilience: Scaling-up Proven Models to Catalyze the $3 Trillion Opportunity’ and was moderated by CBI’s Director of Strategic Programmes, Ujala Qadir. Before jumping into the discussion, Ms. Qadir asked panellists to share how climate change has personally impacted their lives within the last year. Several panellists spoke about their experiences with increased rainfall, flooding, extreme heat, landslides and hurricanes which set the tone for the panel discussion and underscored the importance of adaptation and resilience. She noted that we already have solutions and the capital, but they needed to be repackaged to direct finance towards adaptation and resilience. Panellist Gerald Evelyn, Invesco’s Senior Client Portfolio Manager, cited the use of blended finance in driving institutional investment towards building resilience in the world’s most climate vulnerable regions. He noted that there has been significant interest from institutional investors in Invesco’s Climate Adaptation Action Fund.

Lasitha Perera, the co-founder and CEO of the Development Guarantee Group, also highlighted the usefulness and opportunity guarantees provide, pointing out that “guarantees have mobilised the most private capital but are the most underused.” He noted that many adaptation and resilience investments, especially in emerging markets, sit in sub-investment grade countries. While simultaneously instilling confidence in investors, guarantees provide access to private finance for investees and countries that are often excluded because traditional institutional investors rely on ratings as an indicator of risk. The conversation then continued to the role of MDBs in scaling up finance for adaptation and resilience in which Xianfu Lu, Consultant on Adaptation and Climate Resilience at AIIB, noted that the capital is already there and MDBs already have several processes in place to track adaptation finance, but these efforts are hindered by a lack of “good projects in the pipeline.” In agreement with Ms. Lu, British International Investment (BII) Managing Director of Climate, Diversity and Advisory, Amal-Lee Amin, pointed out that while development finance institutions (DFIs) and MDBs can help build out the pipeline, governments needed to work on creating ‘enabling environments’ for project development. She also noted the importance of collaboration in managing risk and building capacity to scale up finance for resilience. Panellists also spoke about the importance of metrics for helping investors to understand and gain greater transparency around resilience issues and needs. In concluding the session, Ujala Qadir cited the usefulness of the Climate Bonds Resilience Taxonomy in helping investors to understand the impact of their investments on building resilience.

Lasitha Perera, the co-founder and CEO of the Development Guarantee Group, also highlighted the usefulness and opportunity guarantees provide, pointing out that “guarantees have mobilised the most private capital but are the most underused.” He noted that many adaptation and resilience investments, especially in emerging markets, sit in sub-investment grade countries. While simultaneously instilling confidence in investors, guarantees provide access to private finance for investees and countries that are often excluded because traditional institutional investors rely on ratings as an indicator of risk. The conversation then continued to the role of MDBs in scaling up finance for adaptation and resilience in which Xianfu Lu, Consultant on Adaptation and Climate Resilience at AIIB, noted that the capital is already there and MDBs already have several processes in place to track adaptation finance, but these efforts are hindered by a lack of “good projects in the pipeline.” In agreement with Ms. Lu, British International Investment (BII) Managing Director of Climate, Diversity and Advisory, Amal-Lee Amin, pointed out that while development finance institutions (DFIs) and MDBs can help build out the pipeline, governments needed to work on creating ‘enabling environments’ for project development. She also noted the importance of collaboration in managing risk and building capacity to scale up finance for resilience. Panellists also spoke about the importance of metrics for helping investors to understand and gain greater transparency around resilience issues and needs. In concluding the session, Ujala Qadir cited the usefulness of the Climate Bonds Resilience Taxonomy in helping investors to understand the impact of their investments on building resilience.

After this, the day continued with even more insightful sessions on the role of finance in advancing sustainable agriculture, the use of sustainable land bonds to finance nature-based carbon capture and storage as well as transparency and reporting in the GSS+ bonds market. In his spirited closing remarks, Sean Kidney invited attendees to share their own reflections on the day’s discussions and reiterated his hopefulness and excitement for the future.

Other Articles

Unlocking the potential of sustainable bonds for financing climate resilience: the Climate Bonds Resilience Taxonomy

Unlocking the potential of sustainable bonds for financing climate resilience: the Climate Bonds Resilience Taxonomy

Today has seen the launch of the Climate Bonds Resilience Taxonomy (CBRT) during New York Climate Week. This exciting development offers the potential to scale up market action on financing climate resilience (also referred to as adaptation) by providing clear and consistent definitions of climate resilience investments – in other words, a common vocabulary for climate resilience financing that can be used by broad range of stakeholders including investors, issuers, regulators and policymakers.

The CBRT builds upon Climate Bonds’ extensive experience of taxonomy development and extends their existing Climate Bonds Taxonomy into the increasingly urgent, but comparatively under-funded, area of climate resilience. Cadlas is pleased to be the Lead Technical Partner on this ground-breaking initiative, having worked closely with Climate Bonds since 2022 to bring in our extensive, practical experience of climate resilience financing.

The sustainable bonds market represents a significant source of financing for sustainable development, with total sustainable bond issuances now exceeding USD 5 trillion. However, only a small fraction of the capital raised through these issuances currently addresses climate resilience. While Climate Bonds’ analysis suggests that around 19% of labelled green bond issuances include climate resilience (or adaptation) as an eligible use of proceeds (UoP), evidence suggests that only a small fraction of this financing is being challenged into climate resilience investments.

Nonetheless, sustainable bonds are potentially a key instrument for mobilizing investment in climate resilience. Since the City of Gothenburg first included adaptation as an eligible UoP in its 2013 green bond issuance, market activity has progressively increased so that today around 2,500 sustainable bonds issuances have included adaptation as an eligible UoP, while a total volume of just over USD 1 trillion. While most of this activity has taken place in Europe, North America and the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region, there is a need for greater action in Africa, Latin America & the Caribbean (LAC), and the Middle East & North Africa (MENA) regions, where sustainable bond volumes with adaptation UoP remain relatively low despite these being some of the most climate-vulnerable regions of the world with significant climate resilience investment needs.

This highlights the need for much greater flows of financing for climate resilience, as the frequency and severity of climate change impacts – and their economic and human costs – continue to accelerate. For example, the United Nations estimates that developing countries need up to 18 times more adaptation finance than is currently provided. Furthermore, at present more than 98% of reported adaptation finance is provided by public institutions such as development finance institutions (DFIs), which highlights the need for much greater action on mobilising private finance for climate resilience.

An important obstacle to private finance mobilisation for climate resilience has been a lack of clarity on definitions and criteria for climate resilience investments. This creates uncertainty for both investors and issuers and hinders the flow of capital. While sustainable finance taxonomies can play an important role in directing private and public investments toward sustainability goals, they have hitherto not given due attention to climate resilience as an investment theme.

To date, climate resilience has tended to take a back seat to climate mitigation (or decarbonisation) objectives in sustainable finance taxonomies, with a lack of consistency in the sectoral coverage and breakdown of climate resilience financing. This has been compounded by process-based definitions that are difficult for users to apply, and a lack of clear eligibility criteria for determining whether an investment is meaningfully contributing to climate resilience.

The CBRT directly addresses these challenges by providing a credible classification system for climate resilience investments. It offers focused, detailed guidance on climate resilience, an area often under-prioritised or addressed only broadly in many existing taxonomies. The CBRT provides clear, consistent and comprehensive coverage of climate resilience investments based on six Climate Resilience Themes. This covers a broad range of investment types ranging from financing the adoption of specific climate resilience measures within investments to financing economic activities that provide A&R solutions.

The CBRT fills a critical market need for a common foundation that helps investors identify and scale up finance for a wide range of investments that genuinely contribute to building climate resilience. It addresses three critical gaps:

- Clear, Science-Based Definitions and Criteria: The CBRT provides clear, science-based definitions and criteria for identifying investments that substantially contribute to climate resilience. This is essential for overcoming the lack of clarity that has hindered resilience finance flows to date.

- Navigating the Regulatory Landscape: The CBRT helps investors and companies navigate the evolving regulatory landscape. It aligns with and advances beyond regulatory standards like the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy, providing a rigorous, globally applicable framework for demonstrating the climate resilience credentials of investments.

- Flexibility and Adaptability: The CBRT has been designed to be flexible and adaptable to diverse country contexts and investor needs. This is crucial for building resilience, which requires tailored approaches that reflect local vulnerabilities and priorities. The format of the CBRT also allows for further improvements and tailoring to be added over time.

The next exciting chapter in the CBRT story begins now, as it begins to be taken up and put to use by issuers, investors, regulators, policymakers and others. The CBRT will not only enhance transparency for investors by eliminating certain information asymmetries but also support the alignment of global capital flows with local resilience needs and opportunities underpinned by rigorous, science-based eligibility criteria.

As Cadlas continues to collaborate with partners across the finance landscape to enhance resilience financing in various country contexts and investor mandates, we are confident in the CBRT’s applicability across multiple use cases – particularly as it relates to the sustainable debt market. By supporting a range of issuers, investors and other participants in applying and using the CBRT, we can enhance the effectiveness and impact of climate resilience investments, driving more capital towards projects that are crucial for adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change.

Cadlas is committed to fostering a resilient future by enabling more informed and impactful investments in climate adaptation and resilience. Stay tuned for more updates on how the CBRT is set to transform the landscape of climate finance.

Other Articles