Sustainability-Linked Financing for Climate Resilience (part 2)

In Part 1 of this Resilience Unpacked series on Sustainability-Linked Financing for Climate Resilience, we explored the largely untapped potential of sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) and loans (SLLs) to drive progress on climate adaptation and resilience. Despite their success in supporting mitigation goals, our research found that these instruments have only rarely been used to target adaptation outcomes. However, the growing application of water-related KPIs in SLBs and SLLs may offer a meaningful entry point for change.

In Part 2, we dig deeper into how water-related KPIs and SPTs are currently used in SLBs and SLLs across different sectors. We’ll examine how these indicators map against industry benchmarks, any emerging trends and practices shaping this evolving landscape.

Assembling the Evidence Base

To understand current practices, we analysed a dataset of 151 SLBs and SLLs issued between 2019 and 2024 that included water-related KPIs. This data was sourced from the Environmental Finance Database. Our research focused on four water intensive but key priority sectors: i) agri-processing, ii) manufacturing & services iii) property & tourism and iv) primary agriculture. After filtering out instruments from sectors outside our scope and transactions without disclosed KPIs, we identified 36 relevant SLBs and SLLs comprising 20 bonds and 16 loans for further analysis.

These transactions span a range of sectors and geographies, offering valuable insight into how water-related targets are structured in real sustainability-linked finance deals. They also provide a practical foundation for assessing the ambition and comparability of these targets against established industry benchmarks.

Anchoring to Benchmarks: What’s Available and What’s Missing

One of the key challenges in assessing SPT ambition is the absence of standardised benchmarks across sectors. To address this, our analysis drew on several existing reference points:

- EU BREFs

These are comprehensive, technical resources that detail the Best Available Technologies (BAT) for a plethora of industries. While the focus is on integrated pollution prevention and control across industries, they often include information on energy, water use and wastewater management. These documents offer granular, production process level industry benchmarks that, while useful, require careful interpretation to avoid misapplication outside their specific industrial context. As a result, we based our analysis on BREF water benchmarks.

- Buildings industry benchmarks

We referenced environmental benchmarks developed by the Better Buildings Partnership (BBP) to support our analysis of the property & tourism sector. These provide practical environmental benchmarks for commercial buildings, such as offices and shopping centres. However, their specificity to commercial buildings such as office blocks and shopping malls means they are not directly applicable to other building types like residential buildings.

- Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) resources

We reviewed water-related data and guidance from the FAO AQUASTAT database as well as other FAO resources to support our analysis of the primary agriculture sector. While rich in information, methodological uncertainties around target-setting in primary agriculture prevented us from fully integrating these benchmarks into our analysis.

Water-Related KPI Categories in Practice

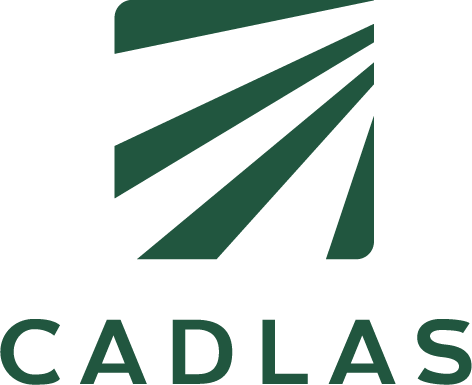

Our analysis revealed that water-related KPIs in SLBs and SLLs generally fall into three main categories: water consumption, water quality, and water reuse/recovery/recycling.

Water Consumption: These KPIs are the most widely used. These may be measured in absolute terms (e.g. cubic metres per year), in relative terms (e.g. percentage reduction in water consumption), or in terms of intensity – for example, water consumption per unit of product in manufacturing, per unit of activity in services, or per square metre in real estate. Some KPIs also focus specifically on water consumption from water-stressed regions, either in absolute or relative terms.

Water Quality: These KPIs tend to focus on the volume of wastewater discharged, either in absolute terms or in specific intensity terms and are commonly cited in BREFs. Some KPIs are qualitative and used to measure the wastewater pollutant load in terms of pollutant quantity or concentration.

Water Reuse/Recovery/Recycling: These KPIs are used in several sectors. These may be framed in absolute, relative, or intensity terms. A few transactions also include rainwater harvesting targets, although these are less common.

Table 1: Categorisation of water-related KPIs identified in the evidence base

Assessing Target Ambition: The Role of Second Party Opinions

In the absence of universally accepted benchmarks, SPTs in SLBs and SLLs are typically assessed by Second Party Opinion (SPO) providers. These providers use qualitative categories such as “insufficiently ambitious,” “moderately ambitious,” “ambitious,” and “highly ambitious” to rate the strength of a given target. While methodologies vary and are not always disclosed in full, two criteria consistently emerge.

First, SPOs often assess whether the target represents a meaningful improvement on the issuer’s past performance. This relies on transparent reporting of historic water use, which can be a challenge for some companies. Second, SPOs consider whether the target exceeds what is typical for the issuer’s sector. This comparative analysis depends on the availability of peer targets or recognised benchmarks, which are uneven across sectors.

Together, these criteria underscore the importance of both internal and external reference points in credible SPT design and the need for more consistent disclosure and benchmarking tools.

Sector-Specific Trends and Observations

The 36 SLBs and SLLs analysed reveal some important sector-level differences in how water-related KPIs and SPTs are used.

In the Agri-Processing sector, most water targets relate to consumption intensity, particularly in the beverage production sub-sector. Here, an ambitious target often involves a 10–20% reduction in water consumption intensity per unit (litre) of product. EU BREFs for the food, drink and milk industries also provide useful benchmarks for wastewater discharge intensity per unit of product, particularly in industries like brewing.

The Manufacturing & Services sector is highly diverse, spanning industries as different as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, paper & packaging, mining and logistics & services. Water KPIs here cover a broad range from water consumption in absolute terms in pharmaceutical production to wastewater discharge intensity in chemicals, plastics & rubber and paper & packaging, as well as water reuse/recovery/recycling in logistics & services. Given this diversity, setting credible targets requires deep industry-specific knowledge and benchmarking.

In the Property & Tourism sector, water consumption intensity is the dominant metric. Here, BBP benchmarks offer a relatively robust reference point for target setting. There is also at least one example of targets related to rainwater harvesting, although such these remain rare.

In contrast, the Primary Agriculture sector remains largely absent from the sustainability-linked finance landscape when it comes to water KPIs. Despite agriculture being the largest consumer of freshwater globally, our analysis found only one SPT in the livestock sub-sector, targeting absolute wastewater discharge. No examples were found for crop production despite it requiring the most significant amounts of water. While the ICMA KPI Registry provides many KPI recommendations, our research found little evidence of their practical use to set SPTs.

Looking Ahead

Our analysis across this Resilience Unpacked series highlights both the progress and the gaps in how water-related KPIs are used in SLBs & SLLs. While levels of rigour and benchmarking vary, what’s clear is that water offers a unique entry point for linking finance to resilience outcomes. Water is deeply connected to the impacts of climate change and increasingly measurable through performance-based metrics making it a natural candidate for integrating adaptation goals into mainstream financial instruments.

If we are to unlock the full potential of sustainability-linked finance for climate resilience, water-related KPIs could help lead the way. They offer a concrete, scalable foundation on which to build stronger, more credible frameworks that channel capital towards adaptation.

Thank you for following along with this Resilience Unpacked series on Sustainability-Linked Financing for Climate Resilience. Stay tuned for more from our Resilience Unpacked insights series and more!

Other Articles

Sustainability-Linked Financing for Climate Resilience (part 1)

Welcome to the second instalment of Resilience Unpacked, Cadlas’ insights series exploring key topics in climate resilience finance. In this edition, we examine sustainability-linked financing and its potential to support greater private investment in climate adaptation.

Results-based financing mechanisms such as Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) and Sustainability-Linked Loans (SLLs) tie financial terms to the achievement of sustainability goals. This creates incentives for companies to meet environmental performance targets. If structured around climate resilience-related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), these instruments could channel much-needed private capital into adaptation measures at the corporate and entity level while setting powerful incentives for improving corporate performance on climate resilience.

Despite their growing popularity in supporting mitigation-focused corporate sustainability goals, SLBs and SLLs rarely incorporate adaptation and resilience objectives. This represents an underutilised opportunity to drive progress on adaptation and resilience. However, there may be important lessons from the application of sustainability-linked instruments in water-related investments that provide avenues for their potential role in financing climate resilience.

What are SLBs and SLLs?

Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) are general-purpose bonds that link financing terms, such as interest rates, to the achievement of predefined sustainability-related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). If an issuer meets or falls short of its sustainability targets, financial terms may be adjusted accordingly.

Sustainability-Linked Loans (SLLs) function similarly but are structured as loans between a given lender and a given borrower, rather than bonds which are issued to raise funds from capital markets. Their terms also adjust based on performance against agreed sustainability KPIs.

Both instruments present an opportunity to incentivise investment in resilience by directly tying financing terms to progress on climate adaptation metrics. However, this opportunity has not been widely utilised across markets.

Limited Usage of Adaptation & Resilience Related KPIs

Despite the surge in sustainability-linked finance, adaptation KPIs remain strikingly rare. Research by Cadlas into global SLB issuances, using the Environmental Finance Database, found no examples of any specific adaptation or resilience KPIs included in global SLB issuances to date.

This trend was also observed in SLLs, with our research finding only one instance of climate adaptation as a KPI. HB Reavis, a UK-based real estate firm, secured a USD 32.4 million SLL in February 2024, which included a KPI linked to the number of EU Taxonomy-aligned buildings designed for climate adaptation. However, limited public information makes it hard to assess the robustness of this KPI.

This scarcity suggests potential uncertainty among issuers about how to define, implement, and measure adaptation KPIs. One key barrier is an unaddressed need for standardised guidance for adaptation-related KPIs in sustainability-linked finance.

Need for Clearer Guidance on Target Setting for Adaptation & Resilience

The International Capital Market Association (ICMA), a globally recognised standard-setting body, currently provides a limited number of KPIs that could convincingly be considered adaptation-related in the June 2024 iteration of its KPI Registry.

These are found in the Energy and Insurance (assets) sectors, representing only two out of ICMA’s twenty-six sectors. Within the Energy sector the adaptation-related KPI related to Share of energy produced in alignment with the EU Adaptation Taxonomy. While the KPI for the Insurance (assets) sector referred to the Proportion of invested assets managed with climate adaptation objectives.

Beyond these, ICMA lists three additional KPIs loosely linked to adaptation and all found within the Utilities (electricity) sector, but these lack clear resilience-focused outcomes. These include:

- Increase additional transformer capacity to facilitate interaction with the grid and integrate renewable energy generation,

- Increase power usage effectiveness/efficiency

- Renewable energy capacity (absolute or proportional).

This highlights the need for more detailed, targeted guidance on adaptation-related KPIs that are suitable for use in sustainability-linked debt instruments. Such guidance could build on existing best practices in financial sector adaptation and resilience metrics, such as the ARIC Adaptation & Resilience Impact Measurement Framework for Investors, developed in collaboration with UNEP-FI and Cadlas.

Water KPIs as a Proxy for Resilience in SLBs and SLLs

While adaptation-focused KPIs remain largely absent, water-related KPIs have gained significant traction, potentially serving as a stepping stone for broader resilience financing.

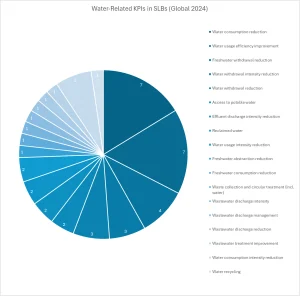

According to the Environmental Finance Database in 2024 there were:

- 43 SLBs valued at nearly USD 72 billion were issued globally with water-related KPIs by corporate borrowers

- The most common KPIs included water consumption reduction, efficiency improvements, and freshwater withdrawal reduction.

While several transactions did not specify precise bond KPIs, SLBs were categorised and grouped based on existing loan KPI details from the Environmental Finance Database and where possible, financing frameworks and other relevant publicly available documents.

Water-Related KPIs in SLBs (Global Issuance, 2024)

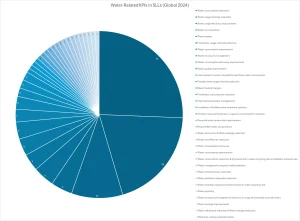

The use of water-related KPIs appeared to be even more prevalent in SLLs, suggesting a stronger link between water management and this approach to sustainability-linked financing.

- 137 SLLs globally included water-related KPIs.

- The total lending volume of these SLLs reached USD 82.0 billion.

Of the one hundred and thirty-seven SLLs tagged by Environmental Finance as having water-related KPIs, only 121 could be categorised.

Water-Related KPIs in SLLs (Global Issuance, 2024)

Water-Related KPIs in the ICMA SLB KPI Registry

The water-related KPIs found in SLBs and SLLs from the Environmental Finance Database align closely with those listed in the ICMA SLB KPI Registry across a wide range of sectors including automotive, construction, energy, food and agriculture, finance, food & beverages, manufacturing, healthcare, maritime, metals & mining, retail, real estate, technology, transportation and utilities.

Across these sectors, water-related KPIs typically fall under six broad categories illustrated in the image below:

Six Categories in the ICMA SLB KPI Registry

These KPIs highlight the capacity for water to be used as a measurable, trackable and financeable resilience theme. However, while these KPIs offer a solid foundation, setting Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs) against them remains a challenge.

From KPI to Impact: Driving Resilience & Improving Investor Confidence

Although water-related KPIs are common, the next hurdle is setting credible Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs). SPTs tend to vary widely by issuer, sector and local context, and there is currently no standardised guidance for setting benchmarks or thresholds, especially for SLLs, where SPTs are rarely disclosed. This limits confidence and consistency across the market.

Despite this uncertainty around benchmarking & target-setting, SLBs still offer a powerful mechanism to incentivise financing broader resilience outcomes including water resource management.

The Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute (AFII) in their article ‘Rebuilding Confidence in the UK Water Sector,’ highlight the role SLBs can play in helping embattled UK water companies drive greater transparency on sustainability challenges, while also providing a financial hedge against poor performance for investors. AFII points out that by directly linking the cost of capital to measurable sustainability targets, water companies can improve investor confidence and build accountability.

Looking Ahead

At Cadlas, we are committed to driving innovation in sustainable finance that supports climate adaptation and resilience. One promising pathway lies in strengthening the design of SLBs and SLLs through more robust and relevant target-setting approaches. Developing clearer guidance for setting SPTs for water-related KPIs could be a practical and high-impact next step. This would not only reinforce the resilience link within SLBs and SLLs but also help build issuer and investor confidence in the adaptation value of these instruments.

By addressing these technical and strategic barriers, sustainability-linked finance can evolve into a more powerful mechanism for mobilising private investment in adaptation and resilience efforts. Water-related metrics, in particular, offer a compelling entry point for advancing this agenda. By anchoring SPTs in credible water-related KPIs, issuers can begin to demonstrate how sustainability-linked finance can deliver measurable adaptation outcomes. In doing so, they can help pave the way for wider market recognition of the role SLBs and SLLs can play in scaling climate resilience.

What’s Next?

In Part 2 of this Resilience Unpacked series on sustainability-linked finance, we’ll take a closer look at how water-related KPIs and SPTs are currently used in SLBs and SLLs across different sectors. We’ll examine how these indicators map against industry benchmarks, as well as analyse emerging trends and practices shaping this evolving landscape.

Other Articles

National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience (Part 2)

Welcome to the second instalment of Cadlas’ new insight blog series, Resilience Unpacked, where we explore key topics in climate resilience financing. In this edition, we focus on National Platforms for Adaptation and Resilience Investment.

National platforms or country platforms for climate action are country-led partnerships that align financing, coordinate stakeholders and connect national climate policies with financeable projects. They enhance collaboration, streamline funding and maximise climate impact by bridging the gap high-level national adaptation plans and financeable investments.

As demand for adaptation finance grows globally, national platforms are increasingly identified as important mechanisms for mobilising investment in climate adaptation and resilience initiatives. Strengthening and expanding these platforms will be key to transforming national climate policy ambitions into investable projects and unlocking the full potential of climate resilience investments for a more resilient future.

In Part 1 of our Resilience Unpacked series on national platforms, we explored exactly what they are and how they function. Now, we’ll take a closer look at their structure, organisation and the key stakeholders driving their work. Click here to read part 1 of this series

Structure of National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience

As explored in Part 1, national platforms for climate action integrate climate considerations into investment pipelines by embedding them into strategy, operations and decision-making processes.

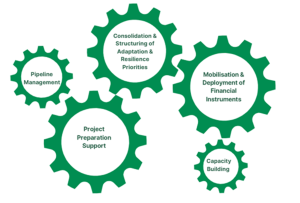

While there is no universal model, these platforms typically achieve their objectives by consolidating national climate priorities, supporting project preparation and capacity building, enhancing project pipeline management and mobilising innovative financial instruments.

A defining characteristic of national platforms is that they are country-driven, meaning their structure varies based on national context. Despite differences in governance and institutional setup, these platforms generally engage a diverse set of stakeholders, including government entities, the private sector, civil society (including academia), and, in many cases, international organisations.

Stakeholder Roles in National Platforms

Stakeholders within national platforms work together to set the platform’s strategic direction, align investments with national adaptation priorities, mobilise funding, and develop investable adaptation project pipelines.

They also build institutional capacity, manage risks, coordinate community engagement to ensure local adaptation needs are met, and streamline funding between national governments and international financial institutions. These stakeholders generally fall into two main categories: leading and supporting stakeholders.

Leading Stakeholders

- Leading stakeholders play a key role in integrating national adaptation priorities into investment planning and financial supervision.

Supporting Stakeholders

- Supporting stakeholders help incorporate adaptation into sectoral investment planning and align community-level adaptation goals with national priorities.

- Depending on the institutional context, there may be other supporting stakeholders which contribute by managing risk and data, aligning projects with finance priorities, coordinating international funding, providing climate risk modelling, and promoting equity in adaptation efforts.

National Platforms in Action: Examples from Around the World

While national platforms have been widely used to support climate mitigation efforts, not many examples exist of their application in scaling up finance specifically for adaptation and resilience. However, international support for adaptation-focused national platforms is growing, with a consortium of MDBs publishing guiding principles for their development and implementation.

Key initiatives driving this momentum include the:

- Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) Climate Adaptation Investment Planning (CAIP) , which helps ADB partner countries translate national adaptation priorities into robust investment programmes by leveraging existing structures and strategies.

- International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF ), which provides long-term financing to help countries strengthen economic resilience to climate risks.

As mentioned previously, the structure of a national platform varies based on country-specific needs and governance models. The following examples illustrate these differences, showcasing distinct stakeholder roles and levels of involvement.

The Netherlands Sustainable Finance Platform

Chaired by the De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), the Netherlands’ Sustainable Finance Platform (SFP) is a great example of a financial sector driven national platform. The SFP brings together stakeholders across the financial sector including asset managers, the Dutch Banking Association, insurers and pension funds to work with government ministries to promote sustainability in the Netherlands through its financial sector.

A core feature of this platform is its working groups, which shape the platform’s thematic focus. Importantly, the SFP features an Adaptation Working Group which examines how the financial sector can support economic adaptation to climate change in four key sectors: built environment, agriculture, industry and transport. The group assesses scenarios, methods, and data required for financial institutions to evaluate climate risks and adaptation needs. While its outcomes are non-binding, its recommendations play an important role in strengthening collaboration between financial institutions, the government, and other stakeholders, ensuring that adaptation challenges are linked to financial sector actions.

The Bangladesh Climate and Development Platform

Bangladesh is among the most climate-vulnerable nations, making climate adaptation finance an urgent priority. Launched in 2023, the Bangladesh Climate and Development Platform (BCDP) is a government-led initiative established in collaboration with international financial institutions, bilateral donors, and the private sector. While not exclusively focused on adaptation and resilience, the platform aims to generate a robust pipeline of climate projects and financing strategies.

Building upon financing from long-term international development financing partners and an arrangement with the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Facility, the BCDP aims to improve the integration of climate risks into fiscal planning, enhance climate-sensitive public investment management and strengthen climate-related risk management for financial institutions. Under the BCDP, a project preparation facility will also be established to enhance project bankability, making climate projects more scalable and attractive to private investment.

The Way Forward for National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience

By streamlining stakeholder collaboration, national platforms have become important mechanisms for mobilising finance for adaptation & resilience. The examples of the Netherlands and Bangladesh highlight how platforms can be tailored to meet country-specific needs to build resilience to the growing challenges of climate change.

As the demand for adaptation finance continues to rise, the success of these platforms will depend on strong, inclusive partnerships and a clear focus on locally led solutions.

This concludes our Resilience Unpacked series on National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience. Thank you for joining us on this deep dive into national platforms and stay tuned for more from the Resilience Unpacked blogs series!

Other Articles

National Platforms for Adaptation & Resilience (Part 1)

Welcome to the first instalment of Cadlas’ new insight blog series, Resilience Unpacked, where we explore key topics in climate resilience financing. In this edition, we focus on National Platforms for Adaptation and Resilience Investment.

We’ll explore how these platforms can serve as crucial mechanisms for financing climate adaptation and resilience initiatives. Specifically, we’ll define what they are and examine how they function, while highlighting the key role they can play in mobilising finance for adaptation and resilience.

What Are National Platforms and Why Do They Matter for Adaptation & Resilience?

National Platforms for climate action, or more commonly called country platforms, are government-led partnerships that bring together multiple stakeholders including the private sector and development finance partners to coordinate efforts, align financing and support national priorities. They act as investment coordination hubs, connecting national climate policies with financeable projects by fostering collaboration, streamlining funding and enhancing the impact of climate-focused development initiatives.

Mobilising Finance for Adaptation & Resilience

Regarded as key coordination mechanisms, national platforms have begun to play an increasingly vital role in advancing national climate goals. Their significance was underscored in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) 2023 Global Stocktake, where they were highlighted as instrumental in facilitating the implementation of the third round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). But how do they relate to adaptation and resilience?

While many of these platforms focus primarily on climate mitigation, such as the International Partners Group (IPG) supported Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), national platforms also have the potential to play a crucial role in scaling up and mobilising finance for adaptation and resilience. They can offer focus and ownership over national and local adaptation priorities and coordinate investment efforts by bridging the gap between high-level adaptation strategies, like National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), and financeable investments.

The diagram below illustrates how national platforms can utilise country-level strategies to align financial flows with adaptation needs:

Mainstreaming Adaptation & Resilience Across the Investment Pipeline

National platforms mainstream adaptation and resilience considerations across the investment pipeline by integrating it into their strategy, operations, and decision-making processes. They achieve this via three key functions: Strategic Planning & Policy Integration, Investment Structuring & Financial Alignment, and Enabling Environments & Capacity Building.

The diagram below illustrates how national platforms function by integrating and mainstreaming adaptation and resilience considerations across the investment pipeline:

Strategic Planning & Policy Integration

National platforms play a vital role in turning national adaptation policies into investable plans and mobilising the necessary domestic and international resources. They create opportunities for government bodies, such as finance ministries, to collaborate with key stakeholders, ensuring adaptation and resilience are embedded into public investment programmes. By translating physical climate risks into investment priorities, they help develop pipelines that align with the risk-return expectations of financiers, making adaptation a more attractive and viable investment.

Investment Structuring & Financial Alignment

National platforms support the structuring of investment programmes that blend public, private and concessional finance to crowd-in commercial capital and ensure that investments meet investor requirements. They also help capture and monetise the full range of adaptation benefits including avoided losses, enhanced resilience and broader sustainable development benefits, strengthening the business case for investment. They also facilitate the integration of adaptation and resilience metrics into investment appraisal frameworks, ensuring that projects can be matched with the right financial instruments and capital types, making it easier to mainstream adaptation into investment decisions.

Enabling Environment & Capacity Building

Beyond finance, national platforms help establish the necessary, enabling environment for adaptation investment through facilitating technical assistance, promoting the development of metrics/standards and promoting the integration of adaptation and resilience into financial supervision. They also play a key role in supporting project preparation, building institutional capacity and fostering knowledge sharing across the financial sector.

Looking Ahead – Strengthening National Platforms for Climate-Resilient Growth

In conclusion, national platforms have the potential to be powerful drivers of adaptation and resilience finance, turning policy ambitions into investable projects.

By integrating adaptation and resilience considerations across the investment pipeline, they foster collaboration, align financial flows and embed adaptation and resilience into national investment decision-making. As the need for adaptation finance continues to rise, strengthening and expanding these platforms will be key to unlocking the full potential of climate resilience investments and building a more climate-resilient future.

To scale climate adaptation finance, national platforms must:

- Expand beyond being primarily mitigation-focused and fully integrate adaptation & resilience

- Align financial flows with adaptation goals for long-term climate security

- Strengthen cross-sector collaboration to foster holistic adaptation strategies

By providing a holistic overview of key stakeholders’ inputs and country needs, national platforms help direct financial flows and facilitate partnerships.

In part 2 of this Resilience Unpacked series on National Platforms, we’ll dive deeper into how National Platforms are structured and organised, and the various kinds of stakeholders that are involved. Stay tuned!

Other Articles